This is an overview of the usage of vec_ptype2() and vec_cast() and

their role in the vctrs coercion mechanism. Related topics:

For an example of implementing coercion methods for simple vectors, see

?howto-faq-coercion.For an example of implementing coercion methods for data frame subclasses, see

?howto-faq-coercion-data-frame.For a tutorial about implementing vctrs classes from scratch, see

vignette("s3-vector").

Combination mechanism in vctrs

The coercion system in vctrs is designed to make combination of multiple inputs consistent and extensible. Combinations occur in many places, such as row-binding, joins, subset-assignment, or grouped summary functions that use the split-apply-combine strategy. For example:

vec_c(TRUE, 1)

#> [1] 1 1

vec_c("a", 1)

#> Error in `vec_c()`:

#> ! Can't combine `..1` <character> and `..2` <double>.

vec_rbind(

data.frame(x = TRUE),

data.frame(x = 1, y = 2)

)

#> x y

#> 1 1 NA

#> 2 1 2

vec_rbind(

data.frame(x = "a"),

data.frame(x = 1, y = 2)

)

#> Error in `vec_rbind()`:

#> ! Can't combine `..1$x` <character> and `..2$x` <double>.One major goal of vctrs is to provide a central place for implementing

the coercion methods that make generic combinations possible. The two

relevant generics are vec_ptype2() and vec_cast(). They both take

two arguments and perform double dispatch, meaning that a method is

selected based on the classes of both inputs.

The general mechanism for combining multiple inputs is:

Find the common type of a set of inputs by reducing (as in

base::Reduce()orpurrr::reduce()) thevec_ptype2()binary function over the set.Convert all inputs to the common type with

vec_cast().Initialise the output vector as an instance of this common type with

vec_init().Fill the output vector with the elements of the inputs using

vec_assign().

The last two steps may require vec_proxy() and vec_restore()

implementations, unless the attributes of your class are constant and do

not depend on the contents of the vector. We focus here on the first two

steps, which require vec_ptype2() and vec_cast() implementations.

vec_ptype2()

Methods for vec_ptype2() are passed two prototypes, i.e. two inputs

emptied of their elements. They implement two behaviours:

If the types of their inputs are compatible, indicate which of them is the richer type by returning it. If the types are of equal resolution, return any of the two.

Throw an error with

stop_incompatible_type()when it can be determined from the attributes that the types of the inputs are not compatible.

Type compatibility

A type is compatible with another type if the values it represents are a subset or a superset of the values of the other type. The notion of “value” is to be interpreted at a high level, in particular it is not the same as the memory representation. For example, factors are represented in memory with integers but their values are more related to character vectors than to round numbers:

# Two factors are compatible

vec_ptype2(factor("a"), factor("b"))

#> factor()

#> Levels: a b

# Factors are compatible with a character

vec_ptype2(factor("a"), "b")

#> character(0)

# But they are incompatible with integers

vec_ptype2(factor("a"), 1L)

#> Error:

#> ! Can't combine `factor("a")` <factor<4d52a>> and `1L` <integer>.Richness of type

Richness of type is not a very precise notion. It can be about richer

data (for instance a double vector covers more values than an integer

vector), richer behaviour (a data.table has richer behaviour than a

data.frame), or both. If you have trouble determining which one of the

two types is richer, it probably means they shouldn’t be automatically

coercible.

Let’s look again at what happens when we combine a factor and a character:

vec_ptype2(factor("a"), "b")

#> character(0)The ptype2 method for <character> and <factor<"a">> returns

<character> because the former is a richer type. The factor can only

contain "a" strings, whereas the character can contain any strings. In

this sense, factors are a subset of character.

Note that another valid behaviour would be to throw an incompatible type

error. This is what a strict factor implementation would do. We have

decided to be laxer in vctrs because it is easy to inadvertently create

factors instead of character vectors, especially with older versions of

R where stringsAsFactors is still true by default.

Consistency and symmetry on permutation

Each ptype2 method should strive to have exactly the same behaviour when the inputs are permuted. This is not always possible, for example factor levels are aggregated in order:

vec_ptype2(factor(c("a", "c")), factor("b"))

#> factor()

#> Levels: a c b

vec_ptype2(factor("b"), factor(c("a", "c")))

#> factor()

#> Levels: b a cIn any case, permuting the input should not return a fundamentally different type or introduce an incompatible type error.

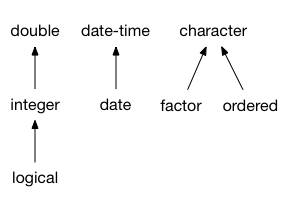

Coercion hierarchy

The classes that you can coerce together form a coercion (or subtyping) hierarchy. Below is a schema of the hierarchy for the base types like integer and factor. In this diagram the directions of the arrows express which type is richer. They flow from the bottom (more constrained types) to the top (richer types).

A coercion hierarchy is distinct from the structural hierarchy implied by memory types and classes. For instance, in a structural hierarchy, factors are built on top of integers. But in the coercion hierarchy they are more related to character vectors. Similarly, subclasses are not necessarily coercible with their superclasses because the coercion and structural hierarchies are separate.

Implementing a coercion hierarchy

As a class implementor, you have two options. The simplest is to create an entirely separate hierarchy. The date and date-time classes are an example of an S3-based hierarchy that is completely separate. Alternatively, you can integrate your class in an existing hierarchy, typically by adding parent nodes on top of the hierarchy (your class is richer), by adding children node at the root of the hierarchy (your class is more constrained), or by inserting a node in the tree.

These coercion hierarchies are implicit, in the sense that they are

implied by the vec_ptype2() implementations. There is no structured

way to create or modify a hierarchy, instead you need to implement the

appropriate coercion methods for all the types in your hierarchy, and

diligently return the richer type in each case. The vec_ptype2()

implementations are not transitive nor inherited, so all pairwise

methods between classes lying on a given path must be implemented

manually. This is something we might make easier in the future.

vec_cast()

The second generic, vec_cast(), is the one that looks at the data and

actually performs the conversion. Because it has access to more

information than vec_ptype2(), it may be stricter and cause an error

in more cases. vec_cast() has three possible behaviours:

Determine that the prototypes of the two inputs are not compatible. This must be decided in exactly the same way as for

vec_ptype2(). Callstop_incompatible_cast()if you can determine from the attributes that the types are not compatible.Detect incompatible values. Usually this is because the target type is too restricted for the values supported by the input type. For example, a fractional number can’t be converted to an integer. The method should throw an error in that case.

Return the input vector converted to the target type if all values are compatible. Whereas

vec_ptype2()must return the same type when the inputs are permuted,vec_cast()is directional. It always returns the type of the right-hand side, or dies trying.

Double dispatch

The dispatch mechanism for vec_ptype2() and vec_cast() looks like S3

but is actually a custom mechanism. Compared to S3, it has the following

differences:

It dispatches on the classes of the first two inputs.

There is no inheritance of ptype2 and cast methods. This is because the S3 class hierarchy is not necessarily the same as the coercion hierarchy.

NextMethod()does not work. Parent methods must be called explicitly if necessary.The default method is hard-coded.

Data frames

The determination of the common type of data frames with vec_ptype2()

happens in three steps:

Match the columns of the two input data frames. If some columns don’t exist, they are created and filled with adequately typed

NAvalues.Find the common type for each column by calling

vec_ptype2()on each pair of matched columns.Find the common data frame type. For example the common type of a grouped tibble and a tibble is a grouped tibble because the latter is the richer type. The common type of a data table and a data frame is a data table.

vec_cast() operates similarly. If a data frame is cast to a target

type that has fewer columns, this is an error.

If you are implementing coercion methods for data frames, you will need

to explicitly call the parent methods that perform the common type

determination or the type conversion described above. These are exported

as df_ptype2() and df_cast().

Data frame fallbacks

Being too strict with data frame combinations would cause too much pain because there are many data frame subclasses in the wild that don’t implement vctrs methods. We have decided to implement a special fallback behaviour for foreign data frames. Incompatible data frames fall back to a base data frame:

df1 <- data.frame(x = 1)

df2 <- structure(df1, class = c("foreign_df", "data.frame"))

vec_rbind(df1, df2)

#> x

#> 1 1

#> 2 1When a tibble is involved, we fall back to tibble:

These fallbacks are not ideal but they make sense because all data frames share a common data structure. This is not generally the case for vectors. For example factors and characters have different representations, and it is not possible to find a fallback time mechanically.

However this fallback has a big downside: implementing vctrs methods for your data frame subclass is a breaking behaviour change. The proper coercion behaviour for your data frame class should be specified as soon as possible to limit the consequences of changing the behaviour of your class in R scripts.